In the movies, pain is glorious. The runner pushing to the edge. The magic of childbirth. The soldier battles impossible odds to conquer. Pain? “Suck, it up, maggot, pain is nature’s way of telling you that you’re alive.” But, to the cancer patient, in the real world? Pain is nature’s way of saying “you may soon be dead.”

For a patient suffering from the dread disease, pain means more than torn tissues, invading needles and post-op wounds. It is more than nerves firing, fractures grinding and constricting bowels. To have pain for a cancer patient is to be reminded of the threat, the danger, the deepest intrusion. It is to be reminded that you are acutely mortal.

Pain threatens not only the body, but the soul. Pain destroys life. It steals not only movement and healing, but hope. It is very hard, perhaps impossible, to truly live, let alone find peace or joy, while gripped with pain from the dread disease. We must control pain.

Nonetheless, we are faced with a crisis of abuse and injury from prescription opioids. Each recent year, almost 20,000 people die in this country from legal narcotics and over 8000 die from heroin addiction, which is often a descent from prescription oxycodone or morphine. Such destruction and waste is unacceptable, and is a true health care catastrophe; it must be resolved. As such, a number of federal, state and local programs are in process to address this problem.

We seem to be caught in a Solomon’s choice. Control pain and people will become addicted and die. Limit access to prescription medications and allow our patients, friends and family to suffer the deepest sort of agony. Our challenge is to avoid significant obstacles to access for desperately needy patients, while we simultaneously we address addiction as a disease to be prevented and when it does occur, requires treatment.

The lion’s share of the responsibility for addressing this crisis falls to prescribing physicians. By practicing safe and adequate prescription procedures, doctors can be the first and major champions both for pain control and abuse prevention.

First, they should confirm the need for these powerful agents in each patient. This means understanding these drugs, both their benefit and risk. While opioids are incredibly valuable and, properly prescribed, safe, often anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic or non-pharmaceutical techniques can be used.

When there is any doubt about how a patient may use prescribed medications, , or if there is question whether the patient is actually taking the drugs, physicians must endeavor to confirm compliance and decrease the risk of deliberate diversion. A number of states now have physician accessible online controlled substance databases. Good practice dictates that prescribers check those databases for patterns of prescription fulfillment, duplication, and falsification, and repeat such inquiries on a regular basis. In areas where online access is not available, a phone call to the local dispensing pharmacy may be extremely valuable.

Prescribers should only write as many doses of medications as are needed. For example, this might be six tablets of Percocet for a patient recovering from a minor injury or surgery, instead of 30 or 40 tablets. The extra pills will lurk in a medicine cabinet awaiting the curious hand of a teenager or anxious adult. If there is a risk that six pills may not be enough, having access to the doctor for renewals is important.

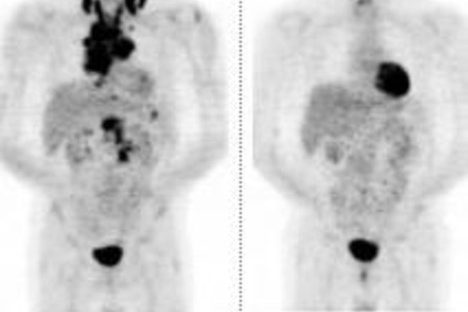

On the other hand, a patient with advanced cancer in continuous pain should never have to worry that they might run out of medication and should have the flexibility to adjust their dosing based on immediate need. Such a patient needs an adequate supply of medication. The risk of addiction or abuse in patients treated for cancer pain is extremely small, therefore our goal must be to preserve access for these needy patients.

It is vital that physicians educate their patients on the proper storage and disposal of drugs, especially addictive medicines. Meds should not be stored in a place where people other than the patient can gain access. It is vital that drugs designed for a patient in need not be stolen or used by unintended individuals who would be at a significantly greater risk for dependence and addiction.

Unused prescriptions should be discarded and destroyed in an effective and safe manner. Many states have “medicine drop” programs where unused medications can be disposed at police stations or hospitals. When it is not possible to discard of narcotics in that way, they should be thrown-out using CDC recommended techniques, such as being mixed with used coffee grounds or moist kitty litter.

The prescription drug epidemic is a complication of needed therapy and we must prevent and treat addiction. At the same time, we must recognize that opioids give patients not only relief, but the opportunity to share each day with their families. They give not only the chance to move, but also the opportunity to hope. When used properly, they give the chance to live.

3 Comments