When is Palliative Care, not palliative care? When it is a secret. When the board certified, experienced and dedicated practitioners of pain control, symptom support and honest communication, believe they are unique. When the average doc is not qualified to administer compassionate treatment. When comfort equals consult.

In 2014, Hospice and Palliative Medicine (HPM) finally became an independent specialty. Now, board certification not only means an interest in palliation and passing an exam, but every new Palliative Medicine doctor must complete a one-year fellowship. This revolutionary advance recognizes, after perhaps a hundred years of neglect, that it is vital to focus on how a patient feels, not just put a label to their malady. Patients are people, not disease carrying organisms.

Nonetheless, the growth and formalization of Palliative Medicine may have a downside. I see the first hints at meetings and on the wards, and worry it may get worse as HPM becomes more sophisticated, data driven and moves from the softness of bedside comfort, to the bright lights of research, publication and guideline driven care. The problem is that primary treating docs, be they oncologists, family doctors, or surgeons, are beginning to hear a disturbing message; palliative care requires subspecialty expertise. More to the point; compassion and symptom control are someone else’s problem.

If a general physician sees a patient with an earache, we would expect them to prescribe drops, or maybe an antibiotic. On the other hand, if that same doctor sees a patient with multidrug-resistant Falciparum Malaria, we would hope she would consult a specialty-trained, board-certified, Infectious Disease consultant.

Such is my view of palliative care. Most symptoms, be it pain, constipation, anxiety, shortness-of-breath, or fatigue, can be soothed with techniques and technology which are well within the skill of most general physicians or specialists, who did not do a Fellowship in Palliative Medicine. Comfort care is a direct extension of the treatment of the primary disease.

There are times, as with Malaria, when one needs the help of a subspecialist in HPM. Intractable pain or complex medications. Agonizing shortness-of-breath. Overwhelming or pathological family dynamics. Ethical conundrums. Combinations of symptoms or illness. Existential terror. When resistant problems threaten quality of life, then it is time to get a Palliative Medicine Consultation and, occasionally, transfer to a HPM service.

This is not a turf war. This is not an oncologist saying, “stay off my land.” Rather, this is about the perspective of the patient and the treating doctor. For the patient and family, the primary treating doctor is the one for whom they have trust and the deepest relationship. The primary caregiver usually has the best understanding of the case. It is that physician who, by their very presence, gives hope and comfort. Losing that natural support when things get worse, is not in the best interest of the patient. It is not acceptable for entire specialties of medicine to send the message, “when things get really bad, I will refer you away.”

The most basic lesson of the hospice and palliative medicine movement is that no matter how bad things get, there is always something the physician can do to give support. This is natural closure for the doctor and balance against the tendency to provide futile care, because they are not sure what else to do. Every doctor must value the control of symptoms and quality of life. To send even a modest message, that this sort of vital care is a someone else’s board-certified specialty problem, is to undermine compassion.

The primary role of the specialty of Palliative Medicine should be to lead all of healthcare towards optimized and improved quality of life. It can do this by doing research and perfecting the techniques. HPM experts should direct Hospice and Palliative Medicine programs. They must guide and teach, developing standards to show us all what can and should be done. HPM must give direct care, but with an emphasis on a collaborative model to protect primary care relationships.

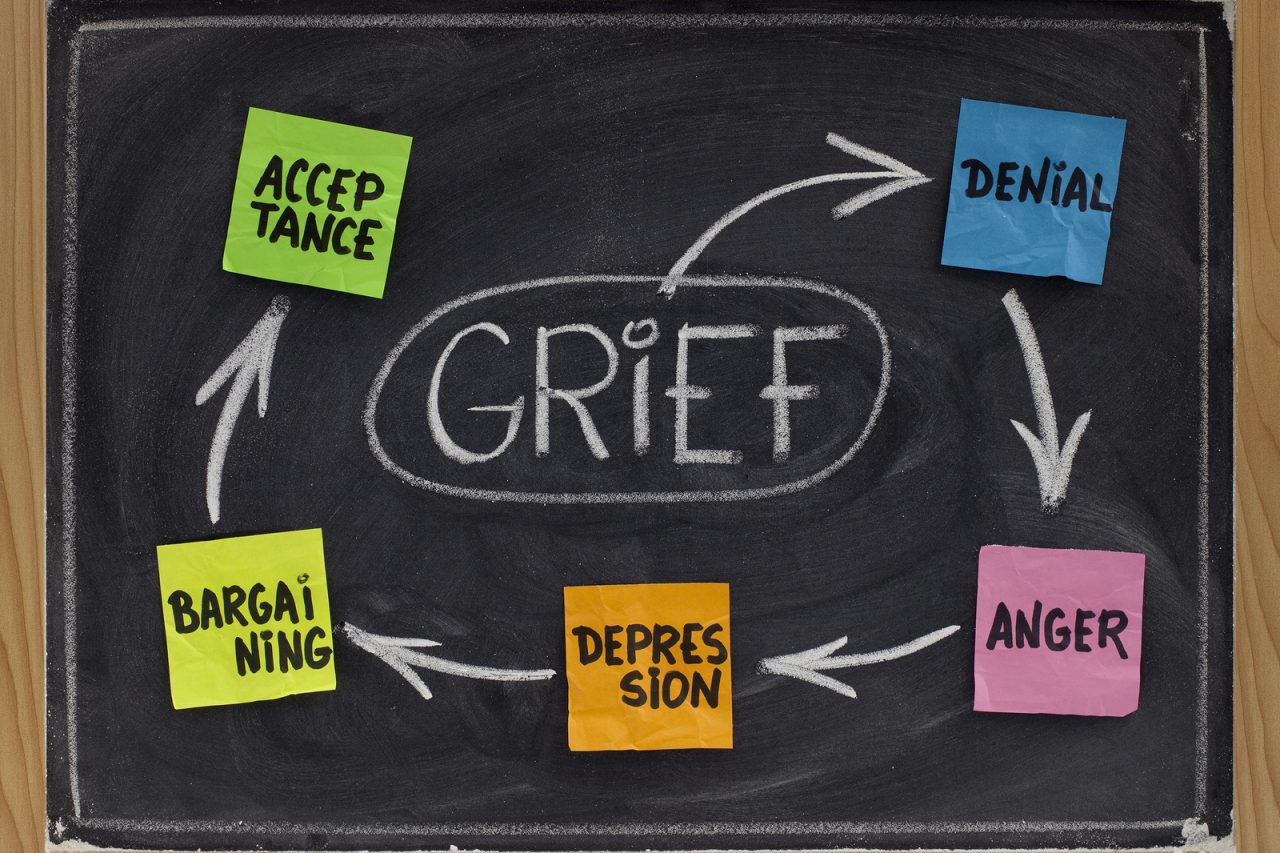

If specialists in Palliative Medicine carve out life quality as their personal fiefdom, this may lead to a paradoxical result. Primary docs will learn that compassionate comfort is no longer their problem. This will result in less focus on palliation and more focus on invasive care. Patients will not receive basic symptom control and may be dumped on HPM services, but only after maximal aggressive intervention has failed. We will roll back to a time before Palliative or even hospice care. Kubler-Ross will turn in her grave.

7 Comments